by Esfandyar Batmanghelidj

For those of us whose job (or hobby) is to understand Iran’s position in the Middle East and in the world, the potential nuclear agreement between Iran and the P5+1 should do more than just change the political and economic landscape we are tasked to analyze. It ought to change the very way we think about Iran.

New York Times columnist David Brooks wrote last week that “Western diplomats have continually projected pragmatism onto their ideological opponents.” In fact, the opposite has generally been true. Though Brooks is correct that “the Obama administration is making a similar projection today” about Iran, it is a recent development, and a break with the policy of the last 36 years.

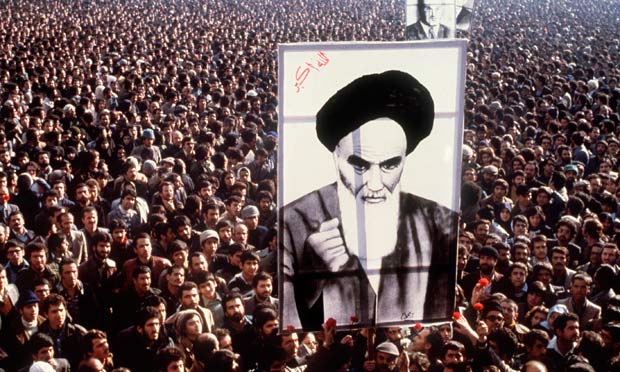

Since the 1979 revolution, political scientists have primarily understood Iran in terms of its prevailing ideology. In other words, they have looked at the country primarily through the country’s Shi’a religion, its system of government, and the unique marriage of the two in the Islamic Republic.

But if a nuclear agreement does come to pass, the community of Iran watchers (and pundits like Brooks) may finally be forced to conclude that theories hinging on ideology really don’t explain what’s going on in Iran (and perhaps even the region at large). If Iran signs a nuclear agreement and adheres to it, the myriad arguments regarding the country’s purported ideological fixations—nuclear proliferation, the export of revolution and terrorism, the destruction of Israel, and so on—would be profoundly shaken, if not disproven altogether. A paradigm shift may well be in the offing.

The Defining Moment

For political scientists and analysts, the 1979 Iranian Revolution was an unexpected and troubling event. Take the case of Harvard political scientist Theda Skocpol. Her seminal work of comparative politics, States and Social Revolutions, posited a general rule that “the repressive state organizations of the pre-revolutionary regime have to be weakened before mass revolutionary action can succeed.” Weakness in state structures, rather than ideology, is the proximate cause of revolutionary upheaval, she argued.

States and Social Revolutions was published in 1979, just months before the fall of the Shah. When Iranian protestors succeeded in ousting their US-backed monarch, political scientists scrambled to understand how a popular uprising could displace such a wealthy and apparently stable ruler. A few years later, as it became clear that the Islamic Republic was here to stay, Skocpol published a paper reevaluating her own theory of revolution. She struggled to explain how the revolution succeeded in the face of an enormous coercive apparatus that was “rendered ineffective without the occurrence of a military defeat in foreign war and without pressures from abroad serving to undermine the Shah’s regime.”

In the course of one journal article, Skocpol made her own States and Social Revolutions obsolete by elevating the importance of ideology over the weakness of state structures. The potent ideology of Shi’a Islam had overpowered one of the strongest states in the world and, in so doing, overturned the arguments of one of the most prominent theorists of revolution.

From the 1979 revolution until today, ideology remains the most important category by which policymakers and analysts understand Iran. According to the dominant narrative in Washington today, Iran is an ideologically motivated state, with a leadership driven by religious zeal and a fanatic hatred of the United States and Israel.

The Perils of Ideology

Yet the focus on Iran’s ideology may perversely make political analysts themselves more prone to the perils of ideology. Consider the case of Council on Foreign Relations senior fellow Ray Takeyh.

In his 2006 book Hidden Iran, Takeyh writes, “It may come as a shock to the casual observer accustomed to American official’s incendiary denunciations of Iran as a revisionist ideological power, to learn that… the Islamic Republic’s policy has been conditioned by pragmatism.” Yet in September 2014, as a nuclear agreement between Iran and the P5+1 seemed within reach, Takeyh co-authored an op-ed, asserting that the “Islamic Republic is not a normal nation-state seeking to realize its legitimate interests but an ideological entity mired in manufactured conspiracies.”

Takeyh’s total reversal highlights a fundamental problem in the way that Iran has been analyzed and understood. Skocpol reversed her theory and championed the role of ideology in response to a world-historical event. But Takeyh’s turn lacks such a real-world antecedent. A Publisher’s Weekly review of his 2011 book Guardians of the Revolution aptly notes, “By failing to acknowledge his own shifting understanding of the situation, Takeyh misses an opportunity to provide a genuinely honest—however inconsistent—assessment.”

There is nothing wrong with analysts changing their views, especially regarding the policy conundrum posed by Iran. But when explanations are totally divorced from material realities, analysts are apt to veer into logical inconsistencies.

For example, Takeyh has long insisted that Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, is “Iran’s most consequential decision-maker,” whose “defiant nuclear stance” makes a nuclear deal with Iran a bad bet because of the high risk of cheating. It’s no surprise, then, that Takeyh describes the likely nuclear deal in a recent Politico piece as a “catastrophic mistake.” But the underlying reason is surprising: Iran’s political structure is “a system permeated by ideology, so Khamenei dying tomorrow is not likely to change the system dramatically.”

On one hand, Takeyh has posited a political system overwhelmingly dominated by the absolute rule of a religious ideologue. On the other hand, he suggests that not even the death of the “most consequential decision-maker” would impact the political calculation surrounding an Iran deal.

The Dangers of Speculation

Since 1979, analysts have devoted a great deal of time and intellectual resources to produce a narrative of how Iran thinks in order to postulate how it behaves. But trying to “get inside the minds” of Iran’s leadership is a fraught task, especially if this is the primary means to understand the American geopolitical relationship with Iran. “It’s hard to know what’s going on in the souls of Iran’s leadership class,” Brooks writes in his recent column, but then he does just that by suggesting that “Iranian leaders are as apocalyptically motivated, paranoid and dogmatically anti-American as their pronouncements suggest they are.” Not only are such efforts inherently speculative, but as a consequence of this approach, analysts themselves risk becoming ideologues.

For example, threats to national security have become ideological constructs, as defined by ideologically motivated actors. The question of the degree to which Iran poses a security risk to US interests is subordinated to the far more subjective question of the extent to which the Iranian regime wants to pose a security risk. Consider the intense debate on the “breakout” time permitted by a final agreement: the time necessary for Iran to produce the material for a nuclear weapon. As Paul Pillar has noted, “The difference between, say, six months and a year is meaningless when any conceivable response, including military attack… could be accomplished within a couple of weeks.” Yet, even though breakout is strategically untenable for Iran, it remains the topic of great consternation, because of an oft-repeated notion that “the Iranians will cheat the way they always cheat” and secretly build a bomb.

The notion that Iran’s leaders make certain decisions, such as the decision to cheat, because it is in their nature to do so, is emblematic of a dangerous tendency. By shifting the analytical focus from capabilities to intent, analysts give themselves the latitude to advise fundamentally disproportionate policy responses, enacted preemptively, with potentially disastrous consequences.

To be fair, those who say Iran cheats point to the historical record to prove their point. Even Under Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, who has been a principal actor in the nuclear negotiations, stated in a 2013 Senate hearing that “we know that deception is part of [Iran’s] DNA” because of the country’s history.

Yet, whereas a structuralist would try to identify the circumstances that made it expedient for Iran to choose deception, those thinking in ideological terms see deception as almost an involuntary urge, part of a deep-rooted cultural propensity. Yet, none of the arms control experts who rely on the cheating explanation in reference to breakout are experts in Iran’s culture. It is what they believe to be true about Iran, rather than what they know that shapes their analysis. We should also remember that regardless of what an Iran watcher may know, they can be paid to believe—or even just say— something else. Eli Clifton has done excellent work investigating this phenomenon.

The lack of academic rigor in the initial understanding of the 1979 Iranian, represented by Skocpol’s reversal, opened the door to the intellectually lackadaisical content of countless policy papers, congressional hearings, and newspaper editorials of the ideologically fixated analysts of today. Yet there is hope. A small cadre of Iran analysts has bucked the trend with laudably levelheaded and holistic analysis. What distinguishes their work is their scrupulous attention to the fine line between belief and knowledge. They construct their analysis and policy recommendations based on what can be objectively and reliably known and argued.

If the Iranian leadership pragmatically decides in favor of a nuclear deal, it would be the great world-historical event necessary to jolt the wider policy community into a new paradigm. Just as 1979 Iranian Revolution forced analysts to devise a post-structural way of thinking about Iran, let us hope that a nuclear agreement will usher in a post-ideological moment, and inspire a new more balanced approach to Iran policy analysis, where objectivity and consistency are once again prized as the hallmarks of the expert.

And they were dragged kicking & screaming to except the results, opposite to the official fear mongering of the established-paid for-stooges and the mass punditry that appear knowledgeable-usually through being bought & paid or by those who have the most to loose if the end result isn’t what they programmed. After all, does the West-the U.S.-really loose, or is it really Netanyahoo and AIPAC and the bought & paid for stooges-traitors-inn the U.S.Congress?

Pardon the spelling mistakes, they were used to make a point, not to claim anything else.

The author states:”In the course of one journal article, Skocpol made her own States and Social Revolutions obsolete by elevating the importance of ideology over the weakness of state structures. The potent ideology of Shi’a Islam had overpowered one of the strongest states in the world and, in so doing, overturned the arguments of one of the most prominent theorists of revolution”

In fact, iran, the state, was tremendously weakened because of

1. a major recession due to misguided economic policies in the last 5 years before the revolution

2. the splintering of the political establishment, in response to the rising dissatisfaction leading to the revolution, between the hardliners and liberals which made an effectice response to the revolution unsuccessful.

The revolution was originally led by intellectuals and students whose ideology was liberal democracy that ayatolloah khomeini promised, as well, in many of his pronouncements before he took over the country.

While ideology was part of the mix for the success of the revolution, it is very incomplete to say that it was the main driver.

People’s dissatifaction, due to major economic downturn, corruption of the regime, the splintering of the political establishment, (due partially to the shah’s advancing cancer) the growing dissatisfaction of the intellectuals,students and the rising middle class and the successful business people with the shah’s authoritarian ways, were major contributors to the success of the revolution along with the promise of the clergy to deliver a more promising future. The fact that outsiders took advantage of the weakened state through many channels including the media is well established.

To state that Iran “was one of the strogest states of the world” at that time is a gross misstatement of the facts.

A very weakened state, the dissatisfaction of the people with their economic situation along with the promise of a better future (whether through liberal democracy or islamic ideology as people understood them at the time) were the main ingredients for the success of the revolution.