As the Iranian leadership prepares to engage in negotiations with the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany (P5+1), the conversation inside Iran has moved beyond the nuclear issue to include a debate about the utility of or need for engaging in direct talks, even relations, with the United States.

Public discussions about relations with the US have historically been taboo in Iran. To be sure, there have always been individuals who have brought up the idea, but they have either been severely chastised publicly or quickly silenced or ignored. The current conversation is distinguished by its breadth as well the clear positioning of the two sides on the issue.

On one side are the hard-liners who continue to tout the value of a “resistance economy” – a term coined by the Leader Ali Khamenei — in the face of US-led sanctions. On the other side is an increasing number of people from across the political spectrum, including some conservatives, who are calling for bilateral talks.

The idea of direct talks with the US was openly put forth last Spring by Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, former president and current chair of the Expediency council, through a couple of interviews. He insisted that Iran “can now fully negotiate with the United States based on equal conditions and mutual respect.” Rafsanjani also conceded that the current obsession with Iran’s nuclear program is not the US’ main problem, arguing against those who “think that Iran’s problems [with the West] will be solved through backing down on the nuclear issue.” At the same time, he called for proactive interaction with the world, and for understanding that after recent transformations in the Middle East, “the Americans… are trying to find “new models that can articulate coexistence and cooperation in the region and which the people [of the region] also like better.” Rafsanjani added that the current situation of “not talking and not having relations with America is not sustainable…The meaning of talks is not that we capitulate to them. If they accept our position or we accept their positions, it’s done.”

In Rafsanjani’s worldview, negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program are merely part of a process that will eventually address other sources of conflict with the US in the region.

Rafsanjani is no longer the lone public voice in favor of direct talks. In fact, as the conversation over talks with the US has picked up, he has remained relatively quiet. Instead, Iranian newspapers and the public fora are witnessing a relatively robust conversation. Last week, for instance, hundreds of people filled an overcrowded university auditorium in the provincial capital of Yasuj, a small city of about 100,000 people, to listen to a public debate between two former members of the Parliament over whether direct talks and relations with the US present opportunity or threats.

On one side stood Mostafa Kavakabian who said

…whatever Islamic Iran is wrestling with in [terms of] sanctions, the nuclear energy issue, multiple resolutions [against Iran] in [international] organizations, human rights violations from the point of view of the West, the issue of Israel and international terrorism is the result of lack of logical relationship, with the maintenance of our country’s principles, with America.

Sattar Hedayatkhah on the other hand argued that “relations with America under the current conditions means backtracking from 34 years of resistance against the demands and sanctions of the global arrogance.”

In recent weeks the hard-line position has been articulated by individuals as varied as the head of the Basij militia forces, Mohammadreza Naqdi, who called sanctions a means for unlocking Iran’s “latent potential” by encouraging domestic industry and ingenuity, and the leader’s representative in the Revolutionary Guard (IRGC), cleric Ali Saeedi, who said that Washington’s proposals for direct talks are a ploy to trick Tehran into capitulating over its nuclear program.

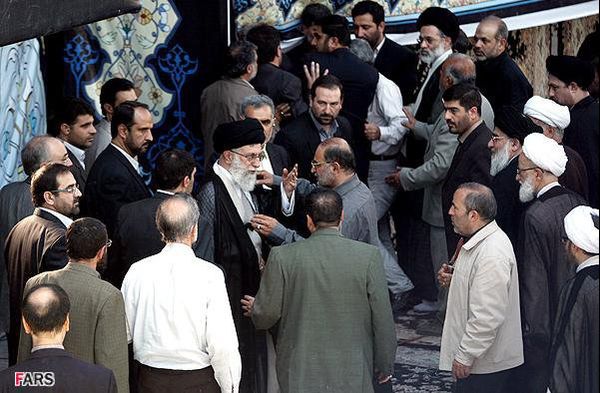

Standing in the midst of this contentious conversation is Leader Khamenei, who, as everyone acknowledges, will be the ultimate decision-maker on the issue of talks with the US. During the past couple of years he has articulated his mistrust of the Obama Administration’s intentions in no uncertain terms and since the bungled October 2009 negotiations over the transfer of enriched uranium out of Iran — when Iran negotiator Saeed Jalili met with US Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs William Burns for the P5+1 side of the meeting — has not allowed bilateral contact at the level of principals between Iran and the US.

Yet the concern regarding a potentially changed position on his part has been sufficient enough for the publication of an op-ed in the hard-line Kayhan Daily warning against the “conspiracy” of “worn-out revolutionaries” to force the Leader “to drink from the poison chalice of backing down, abandoning his revolutionary positions, and talking to the US.” The opinion piece goes on to say that

…by offering wrong analyses and relating all of the country’s problems to external sanctions, [worn-out revolutionaries] want to make the social atmosphere inflamed and insecure and agitate public sentiments so that the exalted Leader is forced to give in to their demands in order to protect the country’s interests and revolution’s gains.

The idea of drinking poison is an allusion to Revolution-founder Ruhollah Khomeini’s famous speech wherein he grudgingly accepted the ceasefire with Iraq in 1988 and refered to it as poison chalice from which he had to drink. Hard-liners in Iran continue to believe that it was the moderate leaders of the time such as Rafsanjani who convinced Khomeini to take the bitter poison, while conveniently omitting the fact that the current Leader Khamenei was at the time very much on Rafsanjani’s side. This time around it is the “worn-out revolutionaries” who, in the mind of the hard-liners, despite being conservative and acting as key political advisors to Khamenei or holding key positions in office, are suspected of pressuring him to accede to talks.

Basirat, a hard-line website affiliated with the IRGC’s political bureau, has taken a different tact and instead of denouncing pressures on Khamenei, has published a list of “Imam” Khamenei’s statements which insist on long-standing enmity with the US. Presumably, the intended purpose is to make it as hard as possible for him to back away from those statements.

The hard-liners face a predicament, which is essentially this: Having elevated Khamenei’s role to the level of an all-knowing Imam-like leader, they have few options but to remain quiet and submit to his leadership if he makes a decision in favor of direct talks. Hence their prior moves to portray any attempt at talks as capitulation at worst, or unnecessarily taking a bitter pill at best.

It is in this context that one has to consider Khamenei’s potential decision over the issue of direct talks. Whether he will eventually agree to them is not at all clear at this point and in fact is probably quite unlikely, unless the US position on Iran’s nuclear program is publicly clarified to include allowance for limited enrichment inside Iran.

In other words, while Khamenei may eventually assent to direct talks, the path to that position requires some sort of agreement on the nuclear standoff — even if only a limited one — within the P5+1 frame and not the other way around.

The reality is that US pressure on Iran has helped create an environment in which many are calling for a strategic, even incrementally implemented, shift of direction in Iran’s foreign policy regarding the so-called “America question.” But this call for a shift can only become dominant if there are some assurances that corresponding and again, even incrementally implemented shifts, are also in the works in the US regarding the “Iran question”.