by Shireen T. Hunter

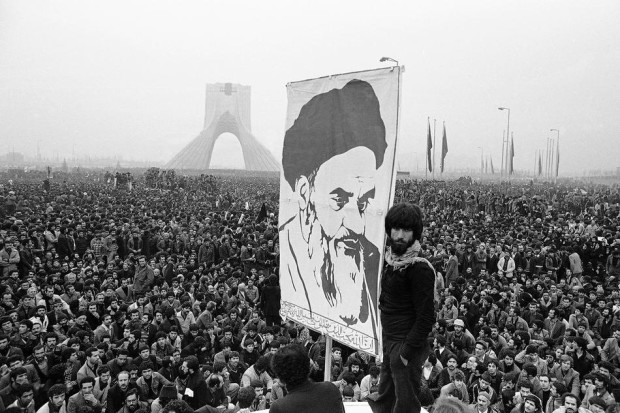

Today Iranians celebrated, observed, or bemoaned the advent of the Islamic Revolution 35 years ago, depending on their cultural and political proclivities.

The revolution’s cultural dimension, its most important aspect, was nothing short of an effort to reshape Iranian identity and hence society and polity according to a new interpretation of Islam. The revolution wiped out the impact of nearly two hundred years of modernization by introducing a far stricter and intrusive Islam into society and peoples’ lives than had ever existed in Iran, even before the advent of modernization. For example, in tales told by foreign visitors, such as the French Chevalier Jean Chardin, who traveled to Isfahan of the Safavid era in the sixteenth century, there is no mention of morality police.

This cultural revolution also undermined Iran’s sense of national unity by attacking non-Islamic aspects of its identity and culture, under the guise of combating nationalist tendencies, and tried to create an identity based on Islamic universalism. This process altered the basis of political legitimacy and created a close linkage between culture and identity on the one hand, and power and legitimacy on the other.

The greatest damage done by these changes was in Iran’s relations with the outside world and in the conduct of its foreign policy. By relegating Iran as a country and nation to second place after Islam and pan-Islamist objectives, the Islamic government severely damaged Iran’s national interests, best demonstrated by Iran’s subjection to unprecedented economic sanctions. Ironically, the revolutionary government failed to gain the support of other Muslim states. Sunni countries continued to see Iran as a Shia and, hence, according to them, a heretic state, and the Arabs dismissed Iran’s Islamic pretentions as insincere and continued to view them as Majus (a derogative name for Zoroastrians) Persians.

Even more consequential was the transformation of Islam from a religion into a state ideology and the creation of a power structure with interests closely linked to the perpetuation of this situation.

Yet is it correct to say that what happened in Iran was really what all the revolutionary forces wanted? Or is it more correct to say that a particular vision of what a post-monarchical Iran should look like, namely the vision of the clerical establishment and some conservative segments of society, triumphed over others?

What happened in 1979 has come to be known as the Islamic Revolution, and in the post-revolutionary period the clerical establishment, together with certain segments of the conservatives classes, have taken credit for ousting the Shah, and the clergy, their families, and entourage. Together with such revolutionary organizations as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), this clerical establishment has been among the principal beneficiaries of the revolution, thus forming Iran’s new religious aristocracy.

Yet the idea that the Islamic Revolution was solely due to religion and the influence of the clergy — paramount among whom was Ayatollah Khomeini — does not quite square with the facts.

The idea of revolution in Iran has been part and parcel of the country’s modernization and the impact of Western ideas, both liberal and socialist. The Constitutional Revolution of 1906 was the direct result of the Iranians’ acquaintance with the democratic movements of Europe and European constitutionalism and nationalism. At that time, the overwhelming majority of the clergy were opposed to constitutionalism, and even those who supported it had a very limited understanding of what it implied. Certainly, even for the more ardent clerical supporters of the Constitutional movement, it did not mean secular rule based on sovereignty of the people.

By the 1920s, socialist ideas were the main wellspring of revolutionary thinking in Iran, a trend that continued throughout the 1970s in various incarnations. It was the socialists who turned Islam into a revolutionary creed and changed it from being a religion into an ideology. The late Ali Shariati was the main, if not the only, figure in this process. He himself has said that his greatest achievement was to change religion into an ideology.

The seminaries of Qom were meanwhile far behind. Shariati gave religion an ideological respectability, appealing to intellectuals and students. He was instrumental in replacing the concept of nation with the Islamic Umma; he attacked Iranian nationalism, and he popularized the concept of an Islamic vanguard in the guise of a new version of Imamate. Fortunately, his speeches are available for all to hear and see.

The secular left also did its bit. It was the left, both religious and Islamic, that introduced the idea of armed struggle and engaged in urban and guerrilla warfare. It was their attacks that first demonstrated the vulnerability of the monarchy, and their intervention played a significant role in the final victory of revolutionary forces. Even the Shah inadvertently popularized the notion of revolution by calling his reforms the White Revolution.

Meanwhile, the liberal and semi-nationalists underestimated both the left and the clerical establishment and, instead of settling for constitutional reform, opted for revolution. It is ironic that very recently Said Hajarian, a major revolutionary figure on the left of the political spectrum, admitted that the Shah was capable of reform. But it is too late for Iran to realize that monarchy can be turned into a constitutional form of government without revolution. It is much more difficult to change an ideologically based system without major upheaval.

The left also bequeathed its foreign policy beliefs to the Islamic regime. The so-called struggle against global arrogance, with its focus on the United States, is a reworked version of the left’s anti-imperialist and anti-American creed, as is the inordinate hostility to Israel and so-called international Zionism, as well as toward conservative Arabs.

For those Iranians who are old enough to remember, imperialism, Zionism, and Arab reaction were the three devils of the Arab left and part of the European left, internalized by Iranian revolutionaries of various stripes. Together with the pan-Islamism of the conservative Muslims, this leftist legacy intensified the unrealistic and destructive dimensions of the Islamic government’s foreign policy.

The left wanted a socialist system with a thin veneer of Islam but got an Islamic system with a thin veneer of socialism and that only at certain periods. Consequently, what has happened after the revolution has been nothing short of a subterranean and more open conflict between the leftist and clerical/conservative elements of the Islamic revolution, as with the 1990s’ struggle over defining the Islamic revolution and Khomeini’s legacy. What has not changed is at least the pretension of allegiance to the revolution and to its so-called ideals, with virtually no one any more quite remembering what the revolution’s ideals were. According to Ayatollah Mesbah Yazdi, revolution was not for a better life but for the revival of Islamic values, while others claim that it was to achieve both goals.

Irrespective of what the revolution’s goals were, today concepts of revolution and counter-revolution are used to promote factional interests, going as far as to undermine the country’s very security, as illustrated by the seemingly ideologically based opposition to Iran’s interim nuclear deal with the P5+1 (the U.S., Britain, France, China and Russia plus Germany). Yet increasingly, it is not ideology that determines factional divisions in Iran, but factional interests that determine the ideological positions of its different actors.

Of course, no country can remain in a perpetual state of revolution, and certainly ideological purity can not be pushed so far as to endanger national survival. The experiences of both the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union support this premise, as in both cases communism was adjusted to the interests of China and Russia.

The question is whether Iran can peacefully manage the transition to a post-revolutionary state. This is not impossible, though it will not be easy. Due to the ideological baggage of the Iranian revolution, legitimacy and power have come to be linked much more closely to ideology than at any other time in Iran’s history. A change in revolutionary ideology would mean a change in the composition of the political elite and the basis of power.

The question then becomes: can the current elite, or significant portions of it, put the interests of the country ahead of their corporate interests and develop a new, non-ideological and inclusive, Iran-based cultural and identity discourse, and thus a popular basis for political power and legitimacy? Failing that, can they at least allow for enough flexibility to avoid future upheavals and save Iran from its current predicament, until the revolutionary fever runs its course? The election of Hassan Rouhani so far offers a glimmer of hope that this might just be possible.

Thank you for this insightful analysis of the Iranian revolution. Whether the regime in Iran can reform itself peacefully or not, the fact remains that any other option, certainly the ones advocated by the hawks in the United States, will be absolutely disastrous. During President Mohammad Khatami’s reformist government there was a great deal of hope that the regime could in fact reform itself from within, but the opposition of hardliners from within and the indifference of the Clinton and the hostility of the Bush Administrations from outside made sure that a most promising reform movement failed. There is always the possibility that a domestic uprising similar to the Constitutional Revolution or the nationalist movement under Dr. Mosaddeq would overpower the government and make it collapse from within. The Green Movement came closest to it, but although it failed it has left its mark and Ruhani’s election was the result. I believe you are right to say that Hassan Rouhani’s election offers a glimmer of hope that this might be possible. His success however depends on a few steps from abroad:

1- Stop threatening Iran and drop the aggressive and illegal mantra, “all options are on the table”. So long as Iranians feel that any move against the regime would open the way for foreign intervention they will support the regime.

2- Stop the sanctions, for they only weaken the middle classes that are the main vehicle for change. They hurt the poorer classes and will strengthen the regime and the revolutionary guards who will control imports and exports.

3- Allow Iranians to travel and study freely in the West, for it is only as the result of greater friendly contacts that people will feel drawn towards the West.

4- Stop fanning the flames of sectarian conflict in the Middle East for it will only result in greater violence rather than strengthening democracy.

5- Trust the Iranian people to do the job, as they have done so many times in the past.

It would be interesting to compare the Iranian Revolutionary Guard with the IRA. Both seem to me to have morphed in time into a sort of ‘mafia’ with economic interests–hence some of the real problems that frustrated peace makers in Northern Ireland for so long. Another parallel organization is the military in Zimbabwe. When most of the Zim army is deployed to Katanga Province to protect Mugabe’s and the generals’ economic (mining and mineral) interests it is telling.

Any comments.

Always interested in reading comments from Farhang, as he sees a different picture then most of us do. Being an outsider, yet aware of the issue[s], presents answers that hadn’t occurred to this individual. I do have to agree with one thing he said quite awhile ago, that being how those in the government, are effected with the power, which does lead to corruption, without a doubt. Thank you also to Ms Hunter for giving a different look at the Iran of today, limited as it be, but if more truth could be told to the vast majority of the people in the U.S., perhaps then, there wouldn’t be such meddling in other countries affairs. Perhaps that is my naive take, but the alternative I see, is doomed to failure for the human race by the warmongers.

“The revolution wiped out the impact of nearly two hundred years of modernization by introducing a far stricter and intrusive Islam into society and peoples’ lives than had ever existed in Iran, even before the advent of modernization.”

I like to know what Ms Hunter considers “Modernization”. Nudity of women? Women painting their faces? Well, if that is what she considers “modernization”, some Iranian women are very much modern since they, especially in Northern Tehran, use plenty of makeup but are not allowed to show too much skin, at least in public. In other words, Ms Hunter is somewhat correct.

Looking at a more appropriate definition of “Modernization”, I would say that Ms Hunter is completely wrong. Modernization can be on the surface or manifest itself in more substantive ways such as progress in science, education, industrialization, agricultural production, development of infrastructure, etc. In that respect, Ms Hunter is completely and categorically WRONG since the Islamic Republic of Iran has surpassed many other countries in the world in every one of these areas that were just listed. During Shah’s period, Iran had a population of less than 30 million and was not under these strict US/EU sanctions pumping 6 million barrels of oil into the world market. However, Iran imported 90 percent of needed products including food.

Check this out:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Science_and_technology_in_Iran

Today, Iran with a population of over 70 million targeted by savage and illegal sanctions has managed to survive strongly and has become self-sufficient in many areas. The country is moving fast to become a totally self-sufficient nation in a few years based on the current rate of progress in real “Modernization”. Over 50 percent of college graduates are women with a high percentage of women occupying sensitive positions in government and industry. In this respect, Islamic Republic of Iran has surpassed all countries in the developing world and compares comfortably with BRIC countries. On that note, I like to leave India out because, considering the miserable living conditions in India as well as women’s position in that corrupt society, I like to think that even Ms Hunter would agree with me. Bride Burning?! Untouchables? Rat People? Dead Bodies on side-walks? Oh come on!! Can we really call India “The Largest Democracy in the World”? Oh boy!!?? What a cesspool of existence…..