by Derek Davison

The three key timelines at the center of the negotiations between world powers and Iran over its nuclear program were the subject of a panel discussion at the Wilson Center today. Jon Wolfsthal of the Center for Nonproliferation Studies spoke about the duration of a hypothetical comprehensive agreement, Daryl Kimball of the Arms Control Association (ACA) discussed Iran’s “breakout” period, and Robert Litwak of the Wilson Center talked about possible timeframes for sanctions relief.

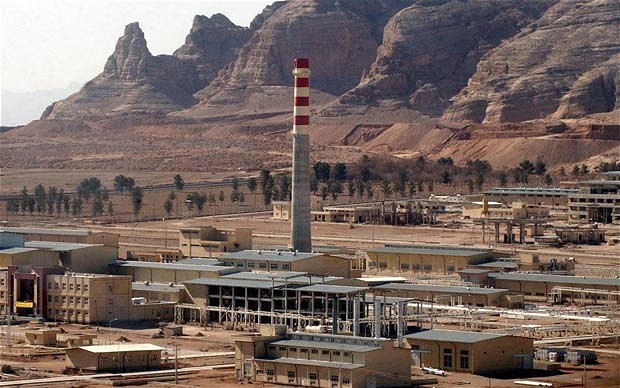

While there may be flaws in the P5+1’s (US, UK, France, China, and Russia plus Germany) decision to make “breakout” their primary focus, it is that timeline, and specifically its uranium enrichment component, that dominates the negotiations and related policy debates. Uranium enrichment capacity is, according to Kimball, the “key problem” in terms of coming to a final agreement, given that more progress seems to have been made between the two parties on limiting the Arak heavy-water reactor’s plutonium production, and on more intensive inspection and monitoring mechanisms. He also discussed the contours of a deal that would allow Iran to begin operating “next generation” centrifuges, which enrich uranium far more efficiently than the older models currently being operated by the Iranians.

Kimball’s suggestion mirrored a new piece in the ACA’s journal by Princeton scholars Alexander Glaser, Zia Mian, Hossein Mousavian, and Frank von Hippel. They proposed a two-stage process for modernizing Iran’s enrichment technology and eventually finding a stable consensus on the enrichment issue. In the first stage, to last around five years, Iran could begin to replace its aging “first generation” centrifuges with more advanced “second generation” centrifuges so long as Iran’s overall enrichment capacity remains constant, and it would be able to continue research and development on more modern centrifuge designs so long as it permitted inspectors to verify that those more advanced centrifuges were not being installed. That five year period would also allow Iran and the international community time to work out a more permanent uranium enrichment arrangement, which could take the form of a regional, multi-national uranium enrichment consortium similar to Urenco, the European entity that handles enrichment for Britain and Germany.

As the authors note, Iran is one of only three non-nuclear weapon states (Brazil and Japan are the others) that operate their own enrichment programs, so the global trend seems to be moving in the direction of these multi-national enrichment consortiums. It is unclear if Iran would agree to this kind of framework, but this piece was co-authored by Mousavian, who has ties to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, suggesting that it could become acceptable to the Iranian government.

One major hurdle in the talks remains Iran’s desire, as noted by Kimball, to be able to fully fuel its Bushehr reactors with domestic enriched uranium by 2021, the year when its deal with Russia to supply fuel to Bushehr runs out. Fueling the Bushehr reactors alone would require vastly more enrichment capacity than the P5+1 would be able to accept, and Iran has plans for future reactors that it would presumably want to be able to fuel domestically as well. The P5+1 negotiators, and well-known non-proliferation organizations including ACA, argue that Iran can simply renew its fuel supply deal with Russia and thereby reduce its “need” for enriched uranium substantially. But from Iran’s perspective, domestic enrichment is its only completely reliable source of reactor fuel. Indeed, Russia has historically proven willing to renege on nuclear fuel agreements in the name of its own geopolitical prerogatives. Any final deal that relies on outside suppliers to reduce Iran’s enriched uranium requirements will have to account for Iranian concerns about whether or not those outside suppliers can be trusted. It’s possible that the kind of enrichment consortium described in the ACA piece will satisfy those concerns.

The other timelines in question, the overall duration of a deal and the phasing out of sanctions, spin off of the more fundamental debate over enrichment capacity, and both revolve around issues of trust. Wolfsthal argued that the P5+1 may require a deal that will last at least until Rouhani is out of office, in order to guard against any change in nuclear posture under the next presidential administration. In his discussion of sanctions relief, Litwak pointed to an even more fundamental question of trust: is Iran willing to believe (and, it should be added, can Iran believe) that the United States is prepared to normalize relations with the Islamic Republic and to stop making regime change the paramount goal of its Iran policy? If the answer is “yes,” then Iran may be willing to accept a more gradual, staged removal of sanctions in exchange for specific nuclear goals, which the P5+1 favors. If the answer is “no,” then Iran is likely to demand immediate sanctions relief at levels that may be too much, and too quick for the P5+1 to accept.

Question for anyone with the answer: “How many countries that have signed the N.P.T., are at breakout status, but haven’t done so”? And what is wrong with the idea of Iran being able to belong to a regional consortium to supply other nations who want to have nuclear power plants, especially with climate change upon the world occurring?

Norman, that only makes sense if Iran were to agree to carbon cutbacks and a severe draw down in oil drilling and refining capacity. The UN’s climate change commission and various environmental groups have signaled that OPEC nations, including Iran, have virtually ignored all calls for carbon reductions. Making the argument that refining more enriched uranium to benefit other countries as justification for increasing centrifuge capacity doesn’t meet any rational benchmark given the evidence. Iran’s stance on increasing centrifuge capacity, which has stalled talks with the West, is nothing more than an effort to preserve the one key centerpiece of its nuclear weapons program which is refining capacity. Iran has demonstrated no need for expanding its capacity given its current energy needs and the West is rightly not buying it.

According to experts the Arak nuclear reactor is out in the open, easily can be taken out, additionally, Iran has no reprocessing capacity to make bomb material out of its spent fuel, or, they also lack the know how and the technology. Arak having been made into a “major” issue does not seem to rate that high in urgency. Also, seemingly, the “run” towards a nuclear bomb and the time it takes is also being blown out of realistic proportions. From what I have had the opportunity to read it seems that there are many steps that need to be taken for a country to be able to have a workable nuclear bomb. They need to have enough fissile material first, but then they have to condensate that to bomb material, something that would take time and requires massive amounts of lower density material, which Iran does not seem to have, or be able to have without everyone knowing about it …. Then, they need to develop a trigger, that also takes a lot of time, and then there is testing, to make sure that all of it works, that takes plenty of time and also once you test one bomb, the whole world will know and surely react! If and when a country after many years achieves the ultimate goal of actually having a bomb…. then, from what has been written, the country needs to miniaturize the device and make it to fit a delivery method. It seems that Iran has neither the fissile material enough to engage in a full blown military nuclear program, nor do they have any triggering device, nor the miniaturization know how, or, a delivery method. To imagine that in two or three months, or for that matter a year or two, they can achieve all of this….. and all under the watchful eyes of IAEA and others (us, EU and Israelis)…. the entire idea seems to be unrealistic, and the “break out bogyman” seems more like a red herring!

I guess no one understood the question[s] I asked, at least so far, the answer[s] I see here. Perhaps others might join in?